John Ringling

The man who would one day build a great circus empire was born on May 31, 1866 in McGregor, Iowa, to August Ringling, a German immigrant harness maker and his wife, Marie Salomé Juliar. He was the second youngest in a family of seven brothers and one sister.

From Wagons to Rail

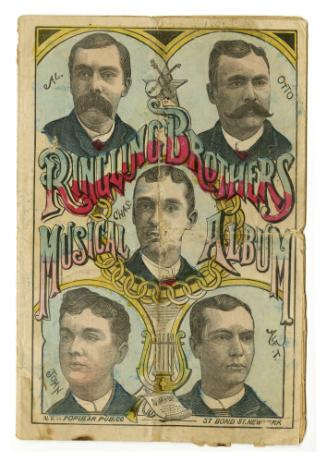

In 1884 five of the brothers, including John, joined with another showman to form “The Yankee Robinson and Ringling Bros. Double Show.” It was the only time they would ever accept second billing. By 1888, they’d become the "Ringling Brothers United Monster Shows, Great Double Circus, Royal European Menagerie, Museum, Caravan, and Congress of Trained Animals" and were charging 50¢ for adults and 25¢ for children.

In 1889, the brothers made the move from animal-drawn wagons to railroad cars and they became the first circus to truly travel the country. Indeed, by 1890 the New York Times described John, who had started with the circus as a clown, and was now acting as its advance man, scheduling, contracting and booking acts as, “a human encyclopedia on road and local conditions.” Later the Ringling Bros. Circus would cross the country in a 100 rail-car caravan each season.

The Making of a Tycoon

In 1905, John married Mable Burton in Hoboken, New Jersey. He was thirty-nine; she was thirty. Two years later the Ringling brothers bought the Barnum & Bailey show for $410,000. It proved a fortuitous investment, as they became the “Kings of the Show World”.

Soon Ringling was investing in railroads, oil, real estate and any number of other enterprises, including Madison Square Garden, where he became a member of the Board of Directors and major investor. In 1925, his personal wealth, holdings and companies were estimated at nearly $200 million.

The Sarasota Years

John’s brother Charles had begun purchasing land in Sarasota, Florida and in 1911 John and Mable purchased 20 acres of waterfront property there. In 1912, they began spending winters in what was then a small town. In the 1920s, they became active in the community and purchased more and more real estate. At one time, John and Charles owned more than 25 percent of Sarasota’s total area.

In Sarasota, John became a formidable force in the Florida land boom of the 1920s, buying and developing land on the Sarasota Keys, where he hoped to create a fashionable winter resort that would rival the popularity of the state’s East Coast resorts. In 1927, he moved the circus’ winter headquarters of the circus to Sarasota from Bridgeport, Connecticut.

The Beginning of the Ringling Collection

Like many wealthy Americans at the turn of the 20th century, the Ringlings made annual trips to Europe, where John found new acts for the circus. Together with Mable and the aid of a Munich art dealer named Julius Bohler, John began collecting art by Old Masters such as Rubens, van Dyck, Velázquez, Tintoretto, Veronese, El Greco, Gainsborough and others that were the beginnings of the extraordinary collection of art that today fills The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art.

They also frequented New York’s more exclusive auction houses, purchasing furnishings, tapestries and paintings from the homes of the City’s socially prominent 400. These pieces, along with the paintings, were displayed in the Ringlings’ homes in New York City, Alpine, NJ and Sarasota. Today, many of these pieces can be found in the Museum of Art and Ca’ d’Zan, the mansion John and Mable built in the Venetian Gothic style they so greatly admired.

The American Circus King

With the purchase of the American Circus Corporation in 1929 for $1.7 million, John, who had taken over the management of The Ringling circus after the death of his brother Charles, now owned most traveling circuses in America. Six feet in height, he was known as a soft-spoken, reserved gentlemen who preferred finely tailored suits, fine cigars and his own private-label bourbon.

Sadly, his reign as “King of the Sawdust Ring” was short-lived. Declining health, over-extended finances, the stock market crash of 1929, and the ensuing Great Depression, as well as an unfortunate second marriage to a young widow, Emily Haag Buck, a year after his beloved Mable’s death, all contributed to his fall.

On December 2, 1936, still marking catalogues for possible purchases and planning a circus spectacle called “Golden are the Days of Memory,” the boy from McGregor who had become the “King of the American Circus” died of pneumonia, at age 70, in his home on Park Avenue, New York.